Chapter 26 – Kapila’s description of Creation (Sāṃkhya Cosmology)

1-2.) Bhagavān continued: I shall now describe, one by one, the unique characteristics of each category (of Prakṛti), through the knowledge of which a person attains complete liberation from the bondage of the modes of Prakṛti.

I shall also explain to you the nature of Knowledge in the form of Self-Realization, which, by cutting the knot of ahaṅkāra (egotism) existing in the heart, leads the jīva to final beatitude—so declare the wise.

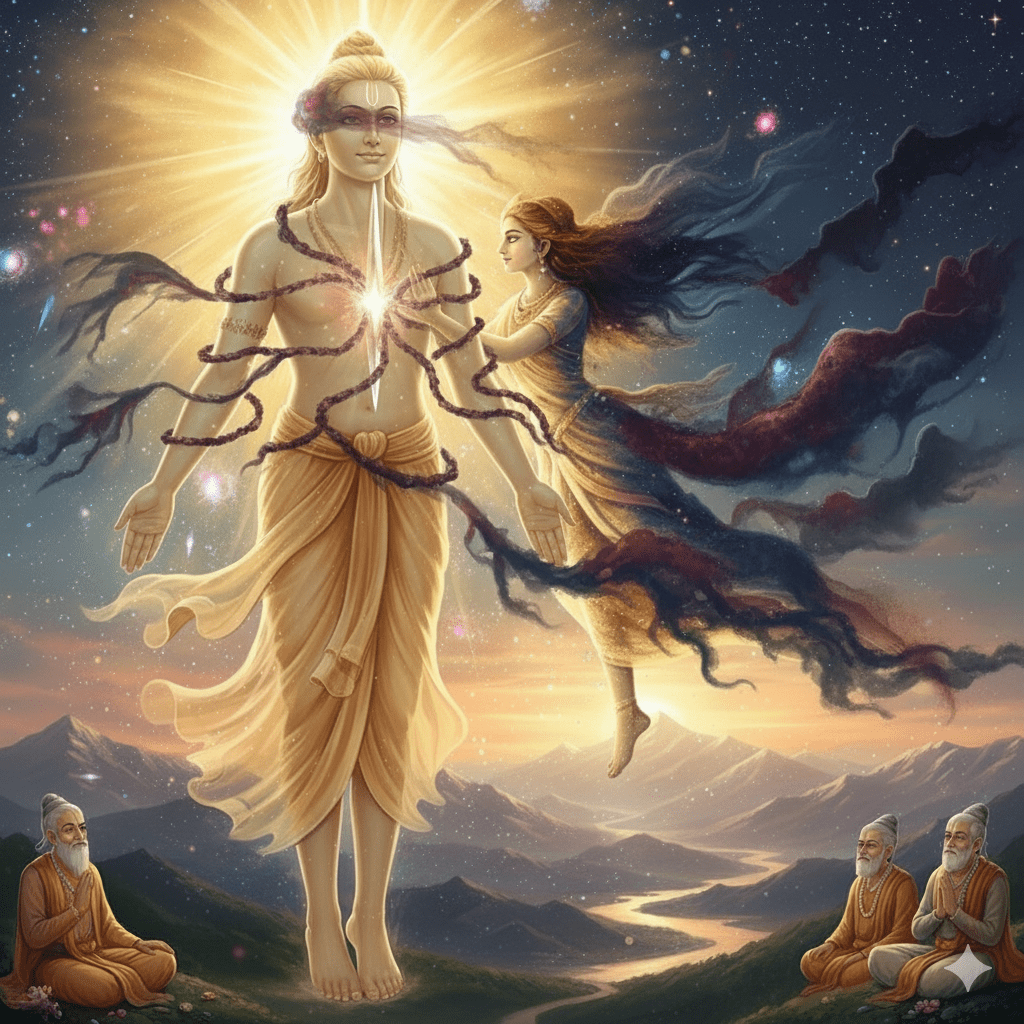

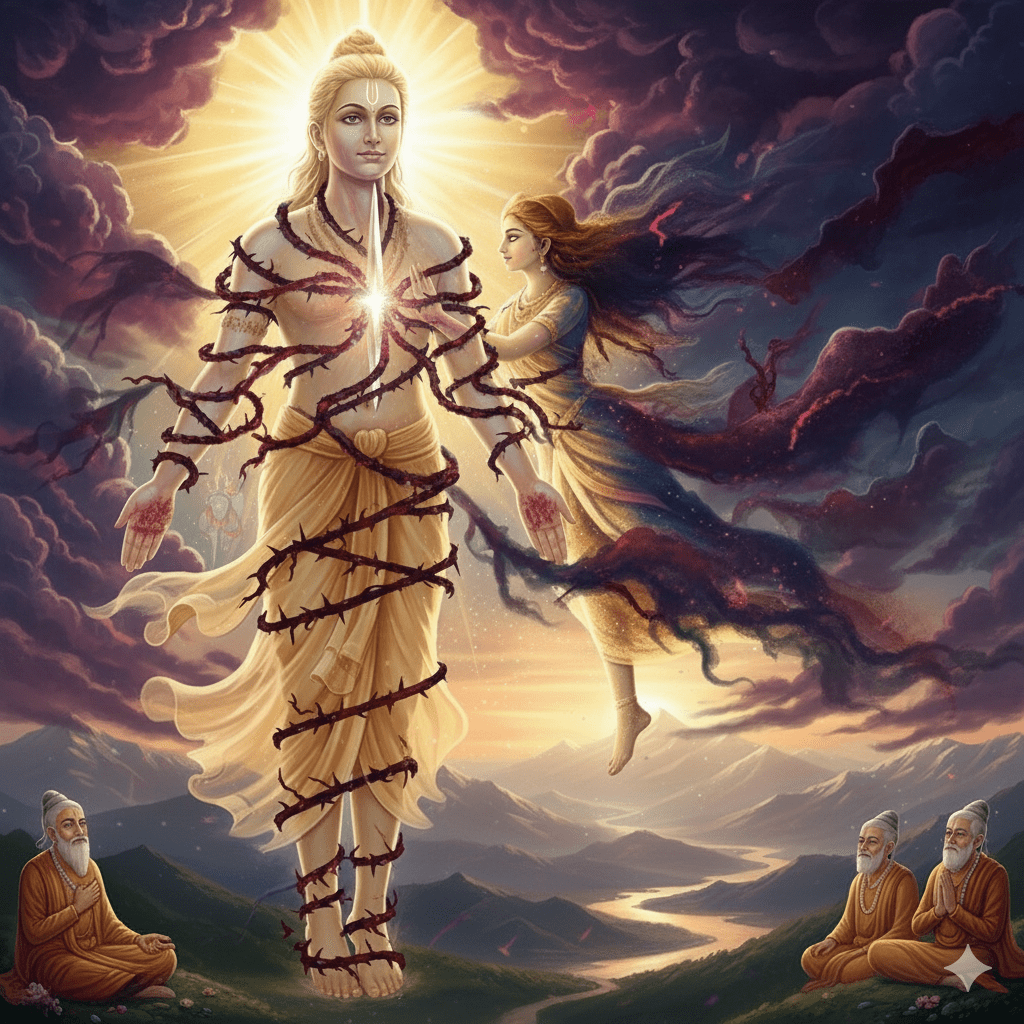

3.) The Puruṣa is no other than the Spirit, who is beginningless, devoid of attributes, existing beyond Prakṛti (Matter), revealed in the heart of all beings and self-effulgent, nay, pervaded by whom the universe presents itself to our view.

4.) This all-pervading Puruṣa, accepted of His own free will the unmanifest divine Prakṛti, consisting of the three guṇas, that sought Him in her playful mood.

5.) Already abiding in Prakṛti, the Puruṣa fell a prey to her charms, that obscure knowledge, and forgot Himself the moment He saw her evolving through her guṇas—sattva, rajas, and tamas—progeny of various kinds with forms conforming to either of the three guṇas. 6.) By identifying Himself with Prakṛti, who is other than Himself, the Puruṣa attributes the doership of actions, which are being performed by the guṇas of Prakṛti, to Himself.

7.) It is this feeling of doership which binds Him to actions, although really speaking, He is a mere witness and therefore a non-doer. And it is this bondage through action which makes Him helpless in the matter of pleasurable and painful experiences, although He is independent in reality, and subjects Him to repeated births and deaths even though He is blissful by nature.

8.) The knowers of Truth recognize Prakṛti as responsible for the identification of the soul with body, with the senses and mind as well as with the agents (the deities presiding over the senses, etc.). As for the experience of pleasure and pain, they hold the Puruṣa (identifying Himself with Prakṛti) to be responsible, although as a matter of fact, He is beyond Prakṛti.

9.) Devahūti said: Kindly also tell me, O Supreme Person, the characteristics of Prakṛti and Puruṣa, the two causes of this universe, which in its gross and subtle forms is nothing but a manifestation of these.

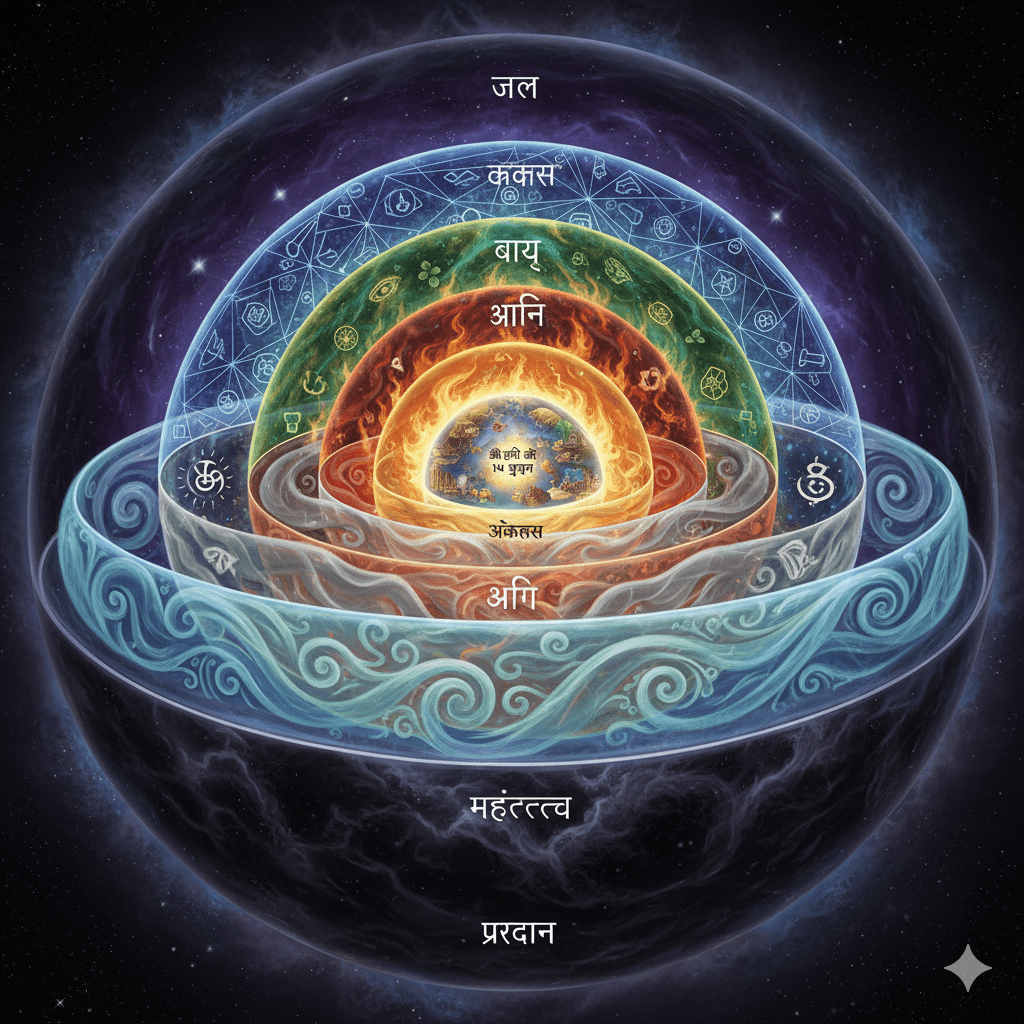

10.) Bhagavān resumed: The wise speak of Pradhāna (Primordial Matter) as Prakṛti—the Pradhāna, which consists of the three guṇas—sattva, rajas and tamas—which is unmanifest and eternal, and exists both as cause and effect, and which, though undifferentiated in its causal state, is the source of distinct categories such as mahat-tattva and so on.

11.) The aggregate of twenty-four categories—viz., the five gross elements, the five subtle elements, the four internal senses, the five senses of perception, and the five organs of action—is known to be an evolute of the Pradhāna.

12-13.) The gross elements are only five, viz., earth, water, fire, air, and ether. The number of the subtle elements too is, in My opinion, just the same: they are smell, taste, colour, touch, and sound. The indriyas (the senses of perception and the organs of action) are ten in number: the auditory sense, the tactile sense, the sense of sight, the sense of taste, the olfactory sense, the organ of speech, the hands, the feet, the organ of generation, and the organ of defecation, which is said to be the tenth.

14-15.) The internal sense is seen to have four aspects in the shape of manas (mind), buddhi (understanding), ahaṅkāra (ego), and citta (reason). Their distinction lies in their functions which represent their characteristics. The disposition of the conditioned Brahma (Brahma conditioned through the guṇas of Prakṛti) has been recognized by the knowers of Truth as consisting of the twenty-four principles just enumerated by Me and no other, kāla (Time) being the twenty-fifth.

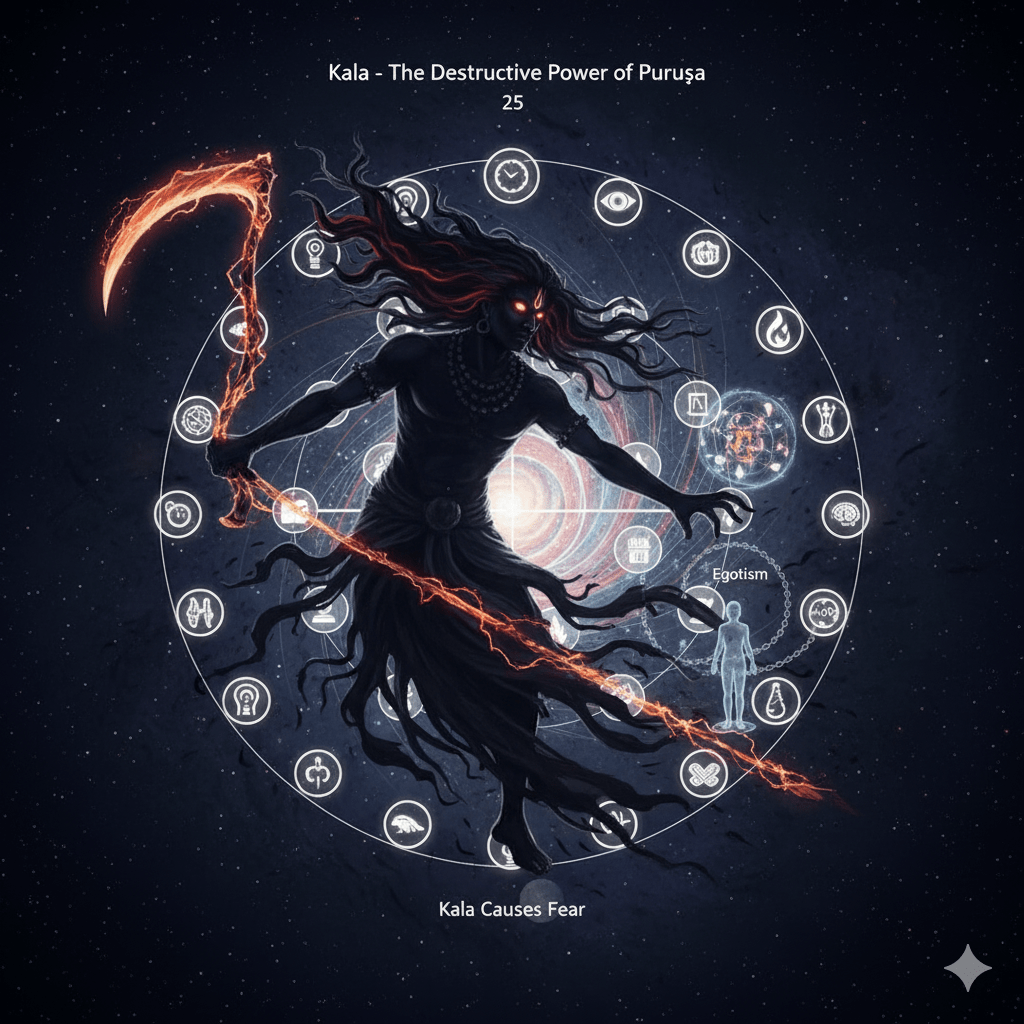

16.) Some people speak of kāla as a potency (destructive power) of the Puruṣa (Paramātmā), which causes fear to the doer (the individual soul) who has come to associate himself with Prakṛti and is deluded by egotism arising out of self-identification with body, etc.

17.) As a matter of fact, O daughter of Svāyambhuva Manu, the Paramātmā Himself, who activates Prakṛti—which is only another name for the equilibrium of the three guṇas, and which in that state admits of no particular name or form—is designated as kāla (Time).

18.) In this way, the Paramātmā Himself, who by His own māyā (wonderful divine energy) abides unaffected within all living beings as the Puruṣa (their Inner Controller) and outside them as kāla, is the twenty-fifth category.

19.) When the Supreme Person placed His energy (in the form of Cit-Śakti or the power of intelligence) in His own Māyā, the source of all created beings, the equilibrium of whose Guṇas had been disturbed by the destiny of the various Jīvas, the Māyā gave birth to the Mahat-tattva (the principle of cosmic intelligence), which is full of light.

20.) The Mahat-tattva, which knew no languor or distraction, and represented the shoot of the tree of the universe, dispelled by its own effulgence the thick gloom (prevailing at the time of universal dissolution)—which had once swallowed the Mahat-tattva—in order to manifest the universe, which lay in it in a subtle form.

21.) Citta (the faculty of reason)—which abounds in the quality of Sattva, is pure and free from passion, and is the place where one can realize Paramātmā—is spoken of as the Mahat-tattva and is also called by the name of Vāsudeva (because it is through the cosmic Citta that they worship Vāsudeva, the foremost of the Bhagavān’s four forms).

22.) Just as water in its natural state (when it is free from foam and ripples), before its coming in contact with earth etc., is clear as crystal, sweet, and unruffled—even so transparency, freedom from languor and distraction, and serenity are predicated of Citta (reason) as its characteristic traits.

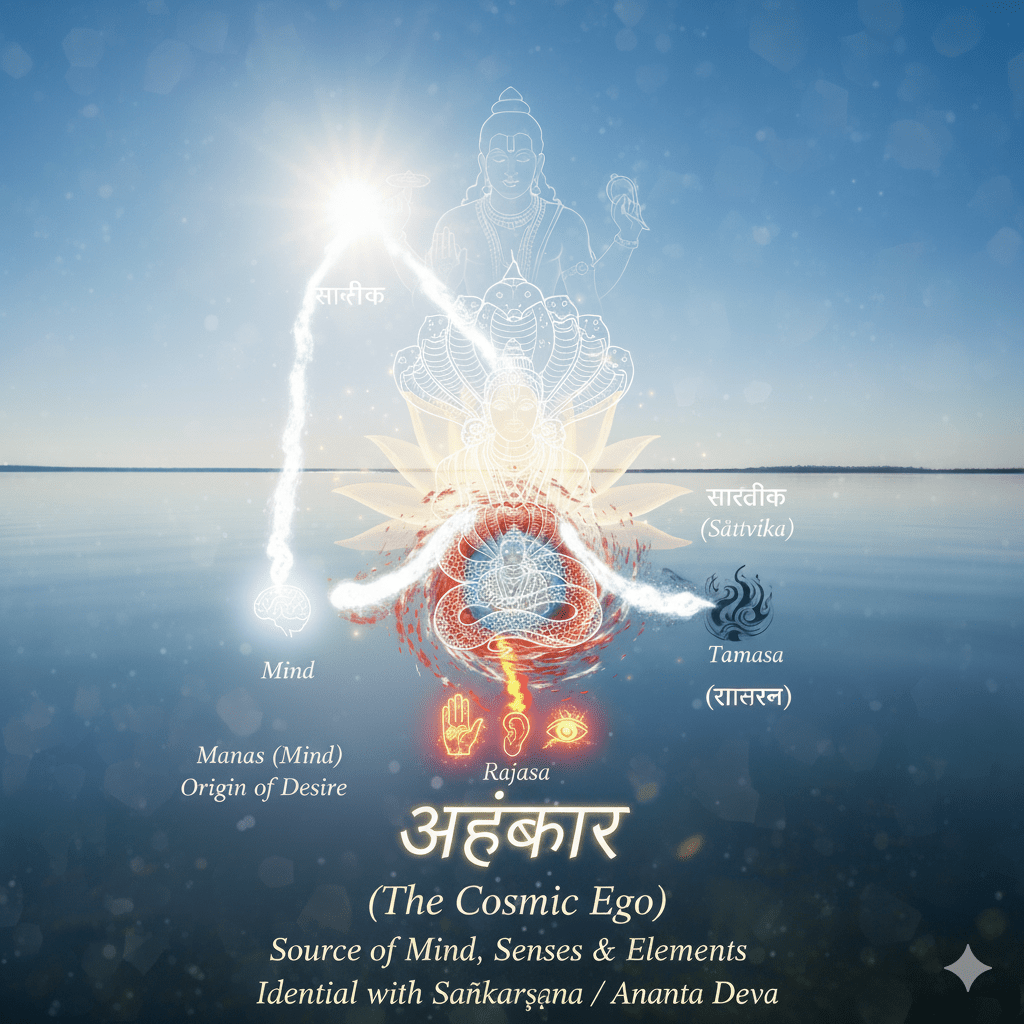

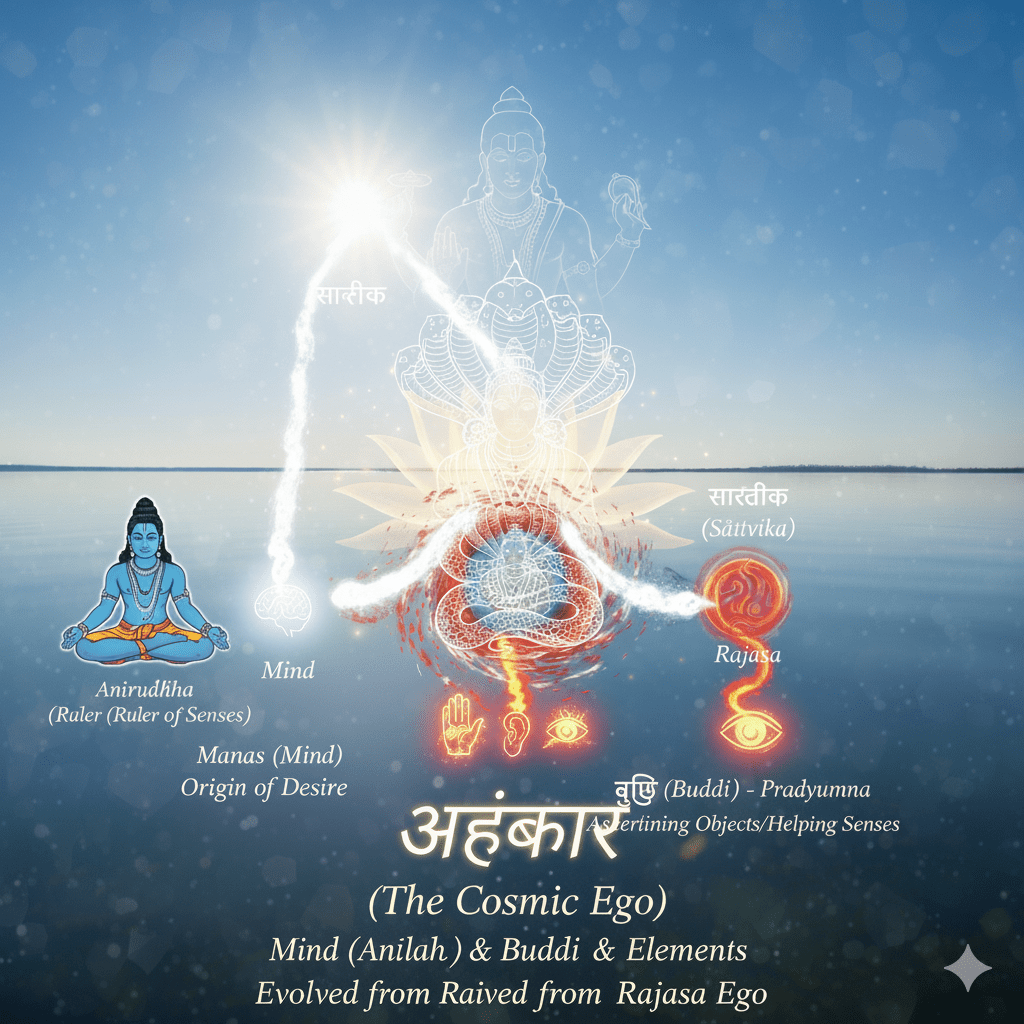

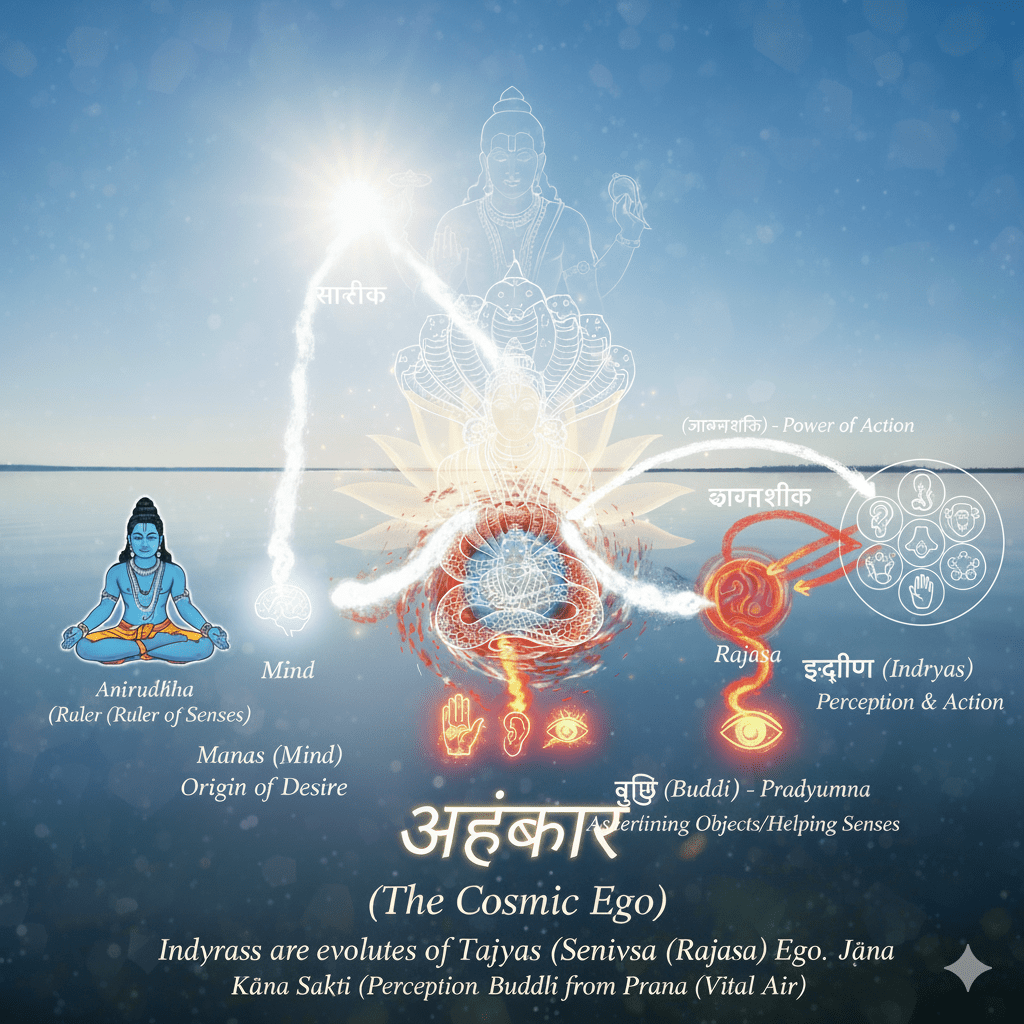

23-24.) From the Mahat-tattva, evolved from the Bhagavān’s own energy (in the form of Cit-Śakti or the power of intelligence), as it underwent transformation, sprang up Ahaṅkāra (the Ego), which is predominantly endowed with active power and is of three kinds—Sāttvika, Rājasa and Tāmasa. From these three types of Ahaṅkāra were severally evolved the mind, the Indriyas (the senses of perception as well as the organs of action) and the gross elements.

25.) This threefold Ahaṅkāra—the source of the gross elements, the Indriyas and the mind, and hence identical with them (because it is the cause which reproduces itself as the effect)—is the same as the Puruṣa called Saṅkarṣaṇa (the second of the four forms of Bhagavān), whom the Vaiṣṇavas speak of as no other than Ananta with a thousand heads.

26.) The Ahaṅkāra is characterized as a doer (when conceived in the form of deities presiding over the Indriyas and the mind), an instrument (in the form of the Indriyas) and an effect (in the form of the gross elements). It is further characterized as serene, active or dull, according as it is Sāttvika, Rājasa or Tāmasa.

27.) From the Vaikārika (Sāttvika) type of Ahaṅkāra, as it underwent transformation, was evolved the mind, whose thoughts and reflections give rise to desire.

28.) It is mind which is known by the name of Aniruddha (the fourth of the four forms of Bhagavān), the supreme Ruler of the Indriyas, who is possessed of a form swarthy as the blue lotus growing in autumn, and who is slowly won by the Yogis.

29.) From the Rājasa ego, as it underwent transformation, sprang up the principle of Buddhi (understanding), O virtuous lady. Ascertaining the nature of objects on their coming to view and helping the senses in their work of perceiving objects—these are the functions of Buddhi (known by the name of Pradyumna, the third form of Bhagavān).

30.) Doubt, misapprehension, correct apprehension, memory, and sleep are said to be the distinct characteristics of Buddhi as determined by their functions.

31.) The senses of perception as well as the organs of action—the two types of Indriyas—are evolutes of the Taijasa (Rājasa) ego alone, since the power of action belongs to Prāṇa (the vital air) and the power of perception inheres in Buddhi (and both these—Prāṇa and Buddhi—are evolutes of the Taijasa ego).

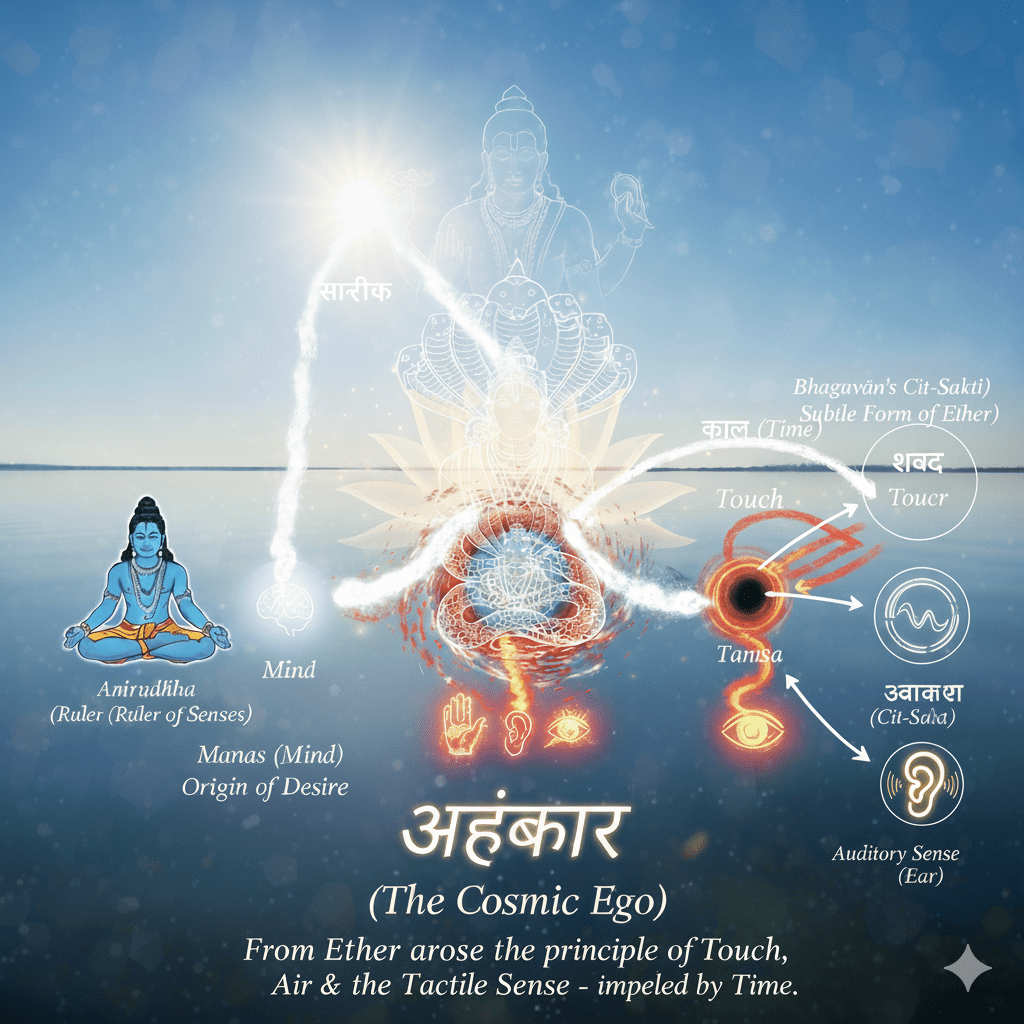

32.) From the Tāmasa ego, as it underwent transformation, impelled by Bhagavān’s energy (Cit-Śakti), sprang up the principle of sound; and from the latter was evolved ether and the auditory sense too, which catches sound.

33.) The knowers of Truth define sound as that which conveys the idea of an object not within sight, indicates the presence of a speaker screened from view, and constitutes the subtle form of ether.

34.) Even so ether is characterized as that which affords room to living beings, gives rise to the notions of inside and outside, and is the abode of Prāṇa (the vital air), the Indriyas and the mind.

35.) From ether, which is an evolute of the principle of sound, as it underwent transformation under the impulse of Time, sprang up the principle of touch and thence air as well as the tactile sense, by which we perceive touch.

36.) Softness and hardness, cold and heat are the distinguishing attributes of touch, and it is further characterized as the subtle form of air.

37.) Even so shaking (the boughs of trees etc.), bringing together things lying apart, having access everywhere, bearing particles of substances containing smell etc. to the olfactory and other senses, carrying sound to the auditory sense, and giving strength and vitality to all the Indriyas—these are the characteristic functions of air.

38.) From air—which is a product of the principle of touch—impelled by the destiny of the various Jīvas, was evolved the principle of colour and thence fire as well as the sense of sight, which enables us to perceive colour.

39.) To appear in the same form as the material substance in which it inheres, to depend for its existence on the substance, to have the same spatial relation as the substance, and to constitute the essential nature of fire—these, O virtuous lady, are the functions of the principle of colour.

40.) To give light, to cook and digest food, to destroy cold, to dry moisture, to give rise to hunger and thirst, and to drink and eat through them—these are the functions of fire.

41.) From fire—which is an evolute of the principle of colour—impelled by the destiny of the various Jīvas, proceeded the principle of taste and thence water as well as the sense of taste, which enables us to perceive taste.

42.) Taste, though one (sweet only), becomes manifold as astringent, sweet, bitter, pungent, sour, and salt, due to contact with other substances.

43.) Even so to wet substances, to bring about cohesion, to cause satisfaction, to maintain life, to refresh by slaking thirst, to soften things, to drive away heat, and to be in a state of incessant supply (in wells etc.)—these are the functions of water.

44.) From water—which is an evolute of the principle of taste—impelled by the destiny of the various Jīvas, proceeded the principle of smell and thence earth as well as the olfactory sense, which enables us to perceive odour alone.

45.) Smell, though one, becomes many—as mixed, offensive, fragrant, mild, strong, acid, and so on, according to the proportion of connected substances.

46.) Even so to give form (through images etc.) to the concept of Brahman (the Infinite); to remain in position without any support other than water etc., which are its causes; to hold water and other substances; to limit the unlimited space through walls of houses; and to manifest the bodies as well as the distinctive qualities (sex etc.) of all living beings—these are the characteristic functions of earth.

47.) The sense whose object of perception is sound (the distinctive characteristic of ether), is called the auditory sense. And that whose object of perception is touch (the distinctive characteristic of air) is known as the tactile sense.

48.) Even so the sense whose object of perception is colour (the distinctive characteristic of fire) is spoken of as the sense of sight. Again, that whose object of perception is taste (the distinctive characteristic of water) is known as the sense of taste. And finally that whose object of perception is odour (the distinctive characteristic of earth) is called the olfactory sense.

49.) Since a cause exists in its effect as well, the characteristics of the former are observed in the latter. That is why the peculiarities of all the elements are found to exist in earth alone.

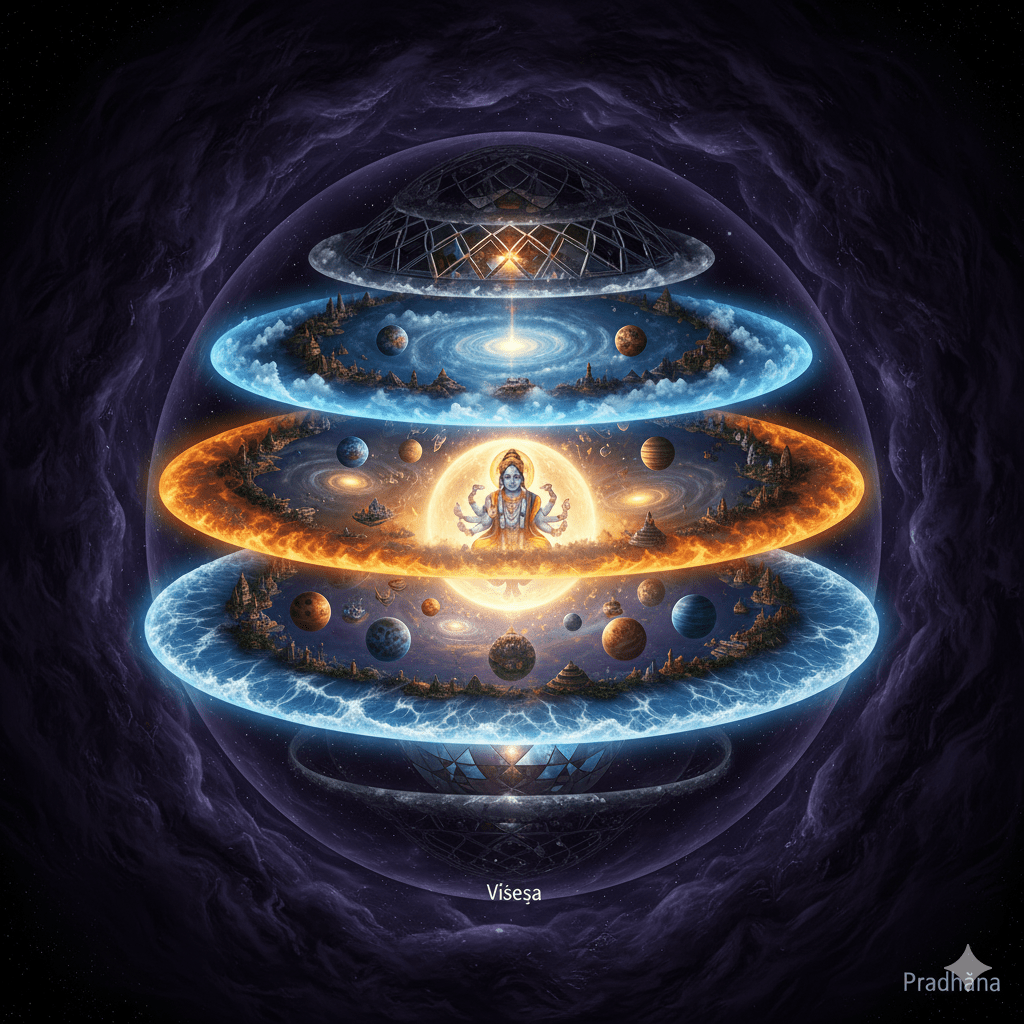

50.) When the Mahat-tattva, the ego and the five gross elements—these seven—stood disunited, Bhagavān Nārāyaṇa (the Cause of the universe) entered them taking with Him Time, the destiny of the various Jīvas and the Guṇas (modes of Prakṛti).

51.) From these seven principles, roused into activity and united by the presence of Bhagavān, arose an unintelligent egg, from which appeared the well-known Cosmic Being.

52.) This egg, which is known by the name of Viśeṣa, is enveloped on all sides by belts of water, fire, air, ether, the ego and the Mahat-tattva, each ten times larger than that which it encloses; and these six being enveloped by the outermost belt of Pradhāna (Primordial Matter). All the fourteen worlds, which are a manifestation of Śrī Hari Himself, are spread within this egg.

53.) Shaking off an attitude of indifference to that shining egg, which lay on the causal waters, the Cosmic Being presided over it and manifested the seats of the various Indriyas out of it.

54.) First of all appeared in Him a mouth and thence came forth the organ of speech and along with it the god of fire (the deity presiding over the organ of speech). Then appeared a pair of nostrils and in them the olfactory sense along with Prāṇa (the vital air).

55.) In the wake of the olfactory sense came the wind-god (the deity presiding over that sense) and thereafter appeared in Him a pair of eyes and in them the sense of sight. In the wake of this sense came the sun-god (the deity presiding over the same) and next appeared in Him a pair of ears and in them the auditory sense, and in the wake of it the Digdevatās (the deities presiding over the directions).

56.) Then appeared in the Cosmic Being the skin and thereon the hair (on the body as well as on the head), a pair of moustaches and a beard. In the wake of these came the herbs and annual plants (the deities presiding over the hair, which represent the sense abiding in the skin), and then appeared in Him an organ of generation.

57.) In the latter appeared the faculty of procreation and thereafter the god presiding over the waters. Next appeared in Him an anus and in the wake of it the organ of defecation and thereafter came the god of death, the terror of the world.

58.) Then sprouted forth in Him a pair of hands and in them the capacity of grasping and dropping things and thereafter came the god Indra (the deity presiding over the hands). Next shot forth in Him a pair of feet and in them appeared the power of locomotion and thereafter appeared Bhagavān Viṣṇu (the deity presiding over that power).

59.) Next appeared in Him the blood vessels and thereafter came forth blood (the power of circulation). In the wake of it came the rivers (the deities presiding over the blood vessels), and then appeared an abdomen.

60.) Next grew therein a feeling of hunger and thirst and in their wake came the ocean (the deity presiding over the abdomen). Then appeared in Him a heart and in the wake of the heart a mind.

61.) After the mind appeared the moon (the deity presiding over the mind) as well as Buddhi (the faculty of understanding); and in the wake of Buddhi came Brahmā (the lord of speech and the deity presiding over Buddhi). Next appeared in Him the ego and thereafter Rudra (the deity presiding over the ego); and last of all appeared in Him a Citta (reason) and then the Kṣetrajña (the Inner Controller, the deity presiding over reason).

62.) When all the aforesaid deities (with the exception of the Inner Controller), though active, were unable to rouse the Cosmic Being into activity, they re-entered each his own seat in order to rouse Him one by one.

63.) The god of fire entered His mouth along with the organ of speech; but the Cosmic Being could not be roused even then. The wind-god entered His nostrils along with the olfactory sense; but the Cosmic Being refused to wake up even then.

64.) The sun-god entered His eyes along with the sense of sight; but the Cosmic Being failed to get up even then. The Digdevatās entered His ears along with the auditory sense; but the Cosmic Being could not be stirred into activity even then.

65.) The herbs and annual plants (the deities presiding over the skin) entered the skin along with the hair on the body; but the Cosmic Being refused to get up even then. The god presiding over the waters entered His organ of generation along with the faculty of procreation; but the Cosmic Being would not rise even then.

66.) The god of death entered His anus along with the organ of defecation; but the Cosmic Being could not be spurred into activity even then. The god Indra entered the hands along with their power of grasping and dropping things; but the Cosmic Being would not get up even then.

67.) Bhagavān Viṣṇu entered His feet along with the faculty of locomotion; but the Cosmic Being refused to stand up even then. The rivers entered His blood vessels along with blood (the power of circulation); but the Cosmic Being could not be made to stir even then.

68.) The ocean entered His abdomen along with hunger and thirst; but the Cosmic Being refused to rise even then. The moon-god entered the heart along with the mind; but the Cosmic Being would not be roused yet.

69.) Brahmā too entered the heart along with reason (Buddhi); but even then the Cosmic Being could not be prevailed upon to get up. Rudra also entered the heart along with the ego; but even then the Cosmic Being could not be made to rise.

70.) When, however, the Inner Controller, the deity presiding over Citta (reason), entered the heart along with reason, that very moment the Cosmic Being rose from the causal waters.

71.) Even as Prāṇa (the vital air), the Indriyas (the senses of perception as well as the organs of action), the mind as well as the understanding are unable to awaken an embodied soul who is fast asleep, by their own power, without the presence of the Inner Controller—similarly they could not do so in the case of the Cosmic Being.

72.) Therefore, through Devotion, dispassion and spiritual wisdom acquired through a concentrated mind, one should contemplate on that Inner Controller as present in this very body, though apart from it.

Thus ends the twelveth discourse entitled “Creation of Rudra, the mind-born Sons and of Manu and Śatarūpā”, in Book Three of the great and glorious Bhāgavata Purāṇa, otherwise known as the Paramahaṁsa-Saṁhitā (the book of the God-realized Souls).