Vision, Foundation, and the Jīva :

In the previous session, we established the overall structure and intent of this deep research study. Now we turn inward—to the lived foundation of Level 1: what it means to become a Yogin within life itself.

The Level 1 Research Study

To support this research study, the Bhagavad Gītā is examined through the complementary frameworks of Yoga Śāstra and Dharma Śāstra. These texts are approached as interpretive lenses that illuminate how discipline, action, responsibility, and inner alignment are cultivated within the world.

Accordingly, the following texts serve as reference frameworks for the Level-1 study:

- Yoga Sūtra — attributed to Ṛṣi Patañjali, providing the foundational psychology of mind, discipline, and inner restraint.

- Yoga Vāsiṣṭha — attributed to Ṛṣi Vālmīki, offering deep insight into lived enquiry, detachment, and discernment within life.

- Sāṅkhya Darśana — attributed to Bhagavān Kapila, clarifying the distinction between consciousness and prakṛti, and the mechanics of bondage and release.

- Haṭha Yoga Pradīpikā — by Ṛṣi Svātmārāma, detailing bodily discipline as a support for steadiness and inner purification.

- Gheraṇḍa Saṁhitā — attributed to Ṛṣi Gheraṇḍa, outlining systematic training of body and mind.

- Śrīmad Bhāgavata Purāṇa — attributed to Ṛṣi Vedavyāsa, offering devotional, ethical, and cosmological perspectives that ground spiritual life in devotion and Dharma.

- Śrī Devī Bhāgavata Purāṇa — attributed to Ṛṣi Vedavyāsa, presenting the principle of Śakti as the dynamic intelligence of life, illuminating how power, responsibility, devotion, and discernment operate within the world.

- Śrī Śiva Purāṇa — attributed to Ṛṣi Vedavyāsa, articulating a vision of the Absolute as the still center of awareness, while exploring renunciation, responsibility, and the yogic attitude within embodied life.

- Manu Smṛti — attributed to Ṛṣi Manu, providing the classical framework of social and ethical order.

- Parāśara Smṛti — attributed to Ṛṣi Parāśara, refining Dharma principles in relation to changing conditions.

It is important to clarify that every concept, principle, and framework examined in this research study must arise directly from the above scriptures. No ideas are introduced on the basis of personal opinion, modern speculation, or interpretive novelty. The role of this study is not to invent a new understanding, but to uncover, organize, and clarify what is already revealed within Sanātana Dharma as expressed in the śāstras.

By allowing Yoga Śāstra and Dharma Śāstra to serve as the sole interpretive foundations, the enquiry remains protected from conceptual confusion and subjective distortion. This discipline ensures that what is studied is not human-constructed theory, but insight grounded in time-tested revelation and lived wisdom. Such an approach brings clarity, consistency, and precision to the study of the Bhagavad Gītā, enabling understanding to translate naturally into lived alignment rather than remaining abstract or unstable.

The Bhagavad Gītā was spoken by Śrī Kṛṣṇa to Arjuna and is received through the śāstric transmission attributed to Sage Vedavyāsa, who is acknowledged in this research study as the original and true author of the Gītā. This study fully recognizes and honors the distinction between speaker and author, and therefore considers Sage Vedavyāsa alone as the authoritative source of the text, without alteration, appropriation, or reassignment of authorship or authority.

King Janaka and the Necessity of Maturation

This is why the ancient dialogue between King Janaka and Śuka, recorded in the Devī Bhāgavata Purāṇa (Book 1, verses 23–30), remains so profoundly instructive for any serious spiritual enquiry. The conversation does not revolve around lofty metaphysical speculation alone; it addresses something far more foundational—the danger of bypassing the natural stages of inner maturation.

King Janaka cautions Śuka against the assumption that dispassion, once intellectually grasped or verbally affirmed, is necessarily complete. Even when vairāgya appears to have arisen, the inner instrument—the mind shaped by habit, memory, and tendency—may still remain unripened by Yoga. Until this maturation occurs, the mind cannot yet be trusted to sustain clarity under the pressures of life. Intellectual clarity alone does not neutralize deeply embedded patterns.

Latent desires (vāsanās) do not dissolve merely because they are understood or dismissed at the level of thought. They persist subtly, resurfacing when conditions are favorable. Their grip loosens not through denial or premature renunciation, but through gradual, lived alignment—where understanding, action, and discipline mature together over time. This is the slow, organic work of Yoga, not the dramatic leap of philosophical assertion.

To illustrate this truth, King Janaka offers a striking and memorable analogy. An ant climbs a tree slowly and deliberately, securing each step before proceeding. Its progress may appear insignificant, yet it is steady and reliable. Birds, by contrast, may rise swiftly and effortlessly, but they tire quickly and must descend before reaching the goal. In the same way, inner mastery does not unfold through sudden declarations of renunciation or premature withdrawal, but through patient progression rooted in stability.

One who leaps too quickly into renunciation, without having integrated clarity into the rhythms of life, risks collapse—manifesting as confusion, suppression, or inner conflict. But one who matures through responsibility, right wisdom, and steadiness as a Yogin develops a foundation that does not regress. Such growth is not dramatic, but it is irreversible.

King Janaka himself stands as the embodiment of this principle. Though fully immersed in the responsibilities of kingship, he demonstrates that liberation is not postponed by engagement with the world when action is rightly oriented. His life affirms that freedom is not a function of external circumstance, but of inner alignment. When success and failure are met with equanimity, when duty is performed without agitation, and when pleasure and pain no longer disturb the inner center rooted in the Ātman, liberation is not something awaited—it is already operative.

Thus, the present enquiry does not ask us to transcend life, escape responsibility, or negate action. It asks us to stand correctly within life—to inhabit action without being consumed by it, to engage fully without losing inner steadiness. Only upon such a foundation can deeper questions arise—not as intellectual speculation, but as direct recognition born of lived clarity.

We Are Not Beginning This Journey Anew — We Are Resuming

We now arrive at a verse that quietly—yet decisively—establishes the foundation of Level 1. It does not announce itself as a philosophical climax, nor does it present a dramatic turning point. Instead, it performs something far more subtle and enduring: it reorients how we understand effort, growth, and spiritual identity itself.

Gītā 6.43 offers a reassurance that gently softens striving and dissolves inner pressure. It reveals something essential—often overlooked in spiritual life:

The practitioner standing here today is not beginning from nothing.

The movement toward Yoga does not arise by chance, sudden enthusiasm, or borrowed inspiration. One turns toward Yoga because a momentum already exists within consciousness itself. Having aligned earlier—perhaps long ago, perhaps forgotten—the Yogin is naturally drawn again toward clarity, integration, and truth.

With this single insight, the Gītā quietly reshapes our understanding of spiritual effort. The practitioner is not a beginner.

Release from the Burden of Being “Behind” :

One of the most subtle burdens carried by sincere practitioners is the feeling of being behind—

– behind others,

– behind where one “should” be,

– behind an imagined spiritual ideal.

This sense of delay quietly breeds anxiety, comparison, and doubt.

The Gītā gently removes this burden. Without drama or flattery, it states:

- You are not late.

- You are not starting from zero.

- You are continuing from where you previously paused.

The movement toward Yoga does not originate in this present embodiment alone. It arises from a deeper continuity of consciousness. Each being stands exactly where their own inner maturation has brought them—no more, no less.

In this vision, there is no hierarchy of practitioners.

– No one is ahead.

– No one is behind.

– There is only continuity unfolding at its own pace.

Inner Recognition, Not New Construction :

Gītā 6.43 points to a truth that is both simple and transformative:

Spiritual growth is not about constructing a new identity.

It is about remembering an inner direction that already exists.

You are not building something foreign.

You are uncovering something intimate.

Yoga is not additive—it is revelatory. Nothing essential is being imported from outside. What unfolds is a clearer recognition of an orientation toward truth that was already present, though perhaps dormant.

In this sense, Yoga is not manufactured.

It is remembered.

Growth is Beyond a Single Lifetime :

Gītā 6.43 releases the practitioner from impatience by correcting a fundamental misunderstanding about growth itself.

There is a widespread assumption—rarely spoken, yet deeply held—that the movement toward liberation must be completed within this very embodiment; that failure to do so necessitates return, bondage, or suffering again. This belief quietly turns spiritual life into a race against time, driven less by understanding and more by a fear of incompletion.

The Gītā does not frame growth in this manner.

Nor does it endorse the idea that inner maturation can be mapped onto a timeline. Spiritual movement is not sequential in the way external achievements are. It does not advance by deadlines, nor does it submit to schedules imposed by the thinking mind.

Gītā 6.43 points elsewhere.

It reveals that consciousness unfolds according to its own intelligence. Growth is neither hurried nor delayed; it proceeds as continuity. The orientation toward Yoga, once established, does not vanish—it resumes. Embodiments change; alignment does not regress.

What feels like effort is often continuity expressing itself.

What appears as striving is frequently remembrance awakening.

This vision neither promotes complacency nor demands urgency. It cultivates steadiness. One walks sincerely, without anxiety about completion, trusting the intelligence of the unfolding itself.

There is no mandate to finish.

There is only continuation.

Consciousness unfolds in rhythm, not in urgency.

The Core Identity Shift of Level 1 :

Here lies the most important transformation introduced at this stage:

You are not trying to become a Yogin.

You are remembering that you already are one.

The work is not to manufacture alignment, but to recognize it. When this is seen, effort softens. Practice becomes natural rather than forced. Discipline becomes continuity rather than pressure.

And comparison—so corrosive to inner growth—falls away almost effortlessly.

Freedom from Comparison and Pressure :

Comparison arises only when we believe growth must look the same for everyone. The Gītā offers a far more humane vision:

Each being unfolds according to their own inner rhythm.

– There is no race.

– There is no borrowed ideal.

– There is no hierarchy of worth.

There is only sincerity, continuity, and attentiveness.

This insight alone releases enormous inner pressure. It allows the practitioner to walk the path with patience, dignity, and trust—grounded not in anxiety about becoming, but in confidence in an unfolding already underway.

In Essence :

Gītā 6.43 quietly reassures us:

- You are not beginning from nothing.

- You are remembering a truth long alive within you.

- You are continuing a journey already in motion.

Level 1 exists for this reason alone—to help you re-enter this remembering consciously.

And with this understanding, the entire path becomes gentler, steadier, and deeply humane.

Key Saṁskṛta Terminologies in This Phase of the Study

Before we proceed further, it is important to establish clarity regarding certain Saṁskṛta terms that will appear repeatedly in the first part of our study. These terms form the conceptual language through which the Bhagavad Gītā communicates its vision. Without a shared understanding of how these words are being used, enquiry can easily become confused or fragmented.

At the same time, this study does not aim to overload the participant with terminology. We will not attempt to introduce every concept at once. Instead, we will work with a limited and functional vocabulary, expanding it gradually as new dimensions of enquiry naturally arise. Terms will be revisited, refined, and deepened over time, rather than fixed prematurely with rigid definitions.

The following terms will be used frequently in Level 1, primarily as orienting concepts, not as final metaphysical conclusions.

Understanding the Jīva

In English usage, the Jīva is often translated as “embodied soul,” “individual soul,” or “self.” In this study, we deliberately refrain from using such terms, not as a stylistic choice, but for philosophical accuracy. The Saṁskṛta term Jīva carries a precise śāstric meaning that cannot be conveyed without distortion when translated into other languages, which import assumptions foreign to the Bhagavad Gītā. Therefore, the Jīva must be referred to only as Jīva. Just as a person’s name does not change to suit convenience, the listener must make the effort to learn the correct term; otherwise, one risks addressing something else while intending the Jīva. Precision in terminology is essential, because when the word is incorrect, the understanding that follows is also misplaced.

Meaning of the Term Jīva :

The Saṁskṛta word Jīva is derived from the verbal root √jīv, meaning to live, to be animated, to function as a living principle.

However, Śāstra never uses Jīva to mean mere biological life, nor does it equate Jīva with just the physical body.

In śāstric usage:

- The body lives because of the Jīva

- The Jīva does not arise because of the body

Thus, Jīva is not a biological category but a metaphysical and experiential principle.

Jīva is Ātman associated with upādhis (limiting adjuncts) arising from Prakṛti.

This definition is crucial and must be seen precisely.

- Ātman is consciousness, unborn, unchanging, svayaṃ-prakāśa (which is revealed by itself and does not require another revealer).

- Upādhis are conditioning factors that limit, localize, and qualify manifestation.

- Prakṛti is the field from which these upādhis arise.

Jīva is not a separate entity from Ātman, nor is it merely Prakṛti.

It is Ātman appearing as an individual locus of experience due to association with Prakṛti-born adjuncts.

To make it simple and easy, let us understand the above definition one by one. First we will learn what is Ātman, then we will see what are the Upādhis, and finally what is Prakṛti.

What is Ātman?

Ātman is consciousness itself.

Not consciousness as a function,

not consciousness as a mental state,

not consciousness as an experiencer—

but consciousness as the very principle of knowing.

Ātman is that because of which knowing is possible at all.

Ātman is:

- Consciousness (cit)

- Unborn (aja)

- Unchanging (avikāra)

- Eternal (nitya)

- Indivisible (akhaṇḍa)

- Self-revealing (svayaṃ-prakāśa)

Ātman does not become aware.

Ātman is awareness itself.

What Ātman Is Not (Neti–Neti Clarity)

To understand Ātman correctly, Śāstra first removes false identifications.

Ātman is not:

- the physical body (gross matter, inert)

- prāṇa or vital force (a function of Prakṛti)

- the senses (instruments of perception)

- the mind (subject to change)

- the intellect (decisive but limited)

- memory, emotion, or personality

- the ego-principle (ahaṅkāra)

All of these are objects of awareness.

Ātman is that by which they are known.

Whatever can be observed cannot be Ātman.

Bhagavad Gītā 2.20 says : “This (Ātman) is never born, nor does it ever die. It does not come into being, nor does it cease to be. Unborn, eternal, ever-existing, ancient— it is not destroyed when the body is destroyed.”

Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad 3.7.23 says : “The Ātman is the inner witness of all bodies and faculties.”

At Level 1, Ātman is not introduced as an abstract metaphysical Absolute, but as a directly recognizable presence—the witnessing awareness that remains unchanged through all states and experiences.

What are the Upādhis & their structure?

The Saṁskṛta term Upādhi literally means: “that which limits, conditions, or qualifies something without actually altering its nature.”

An upādhi does not change Ātman, but it makes Ātman appear as something it is not. Upādhis do not exist independently of Ātman; they depend upon Ātman for their very existence and illumination.

Easy analogy to understand this :

- Space inside a pot appears “small”

- Space itself is never limited

- The pot is the upādhi

Likewise:

- Ātman appears limited, individual, acting

- Ātman itself is never limited

- The body–mind complex is the upādhi

Upādhis are attributes belonging to Prakṛti, falsely superimposed upon Ātman through ignorance.

Because of upādhis:

- the infinite appears finite

- the actionless appears as a doer

- the indivisible appears divided

- the non-individual appears individual

Without upādhis:

- there is no Jīva

- no bondage

- no saṁsāra

- no ignorance to be removed

Why upādhis are necessary for experience :

Ātman by itself:

- does not act

- does not experience

- does not choose

- does not suffer

- does not seek

Yet experience undeniably occurs.

That experience requires:

- instruments

- faculties

- memory

- continuity

- causality

All of this belongs not to Ātman, but to upādhis.

Thus: Upādhis are the functional conditions that allow consciousness to appear as an individual experiencer, without altering its own nature.

Three Layers of Upādhis

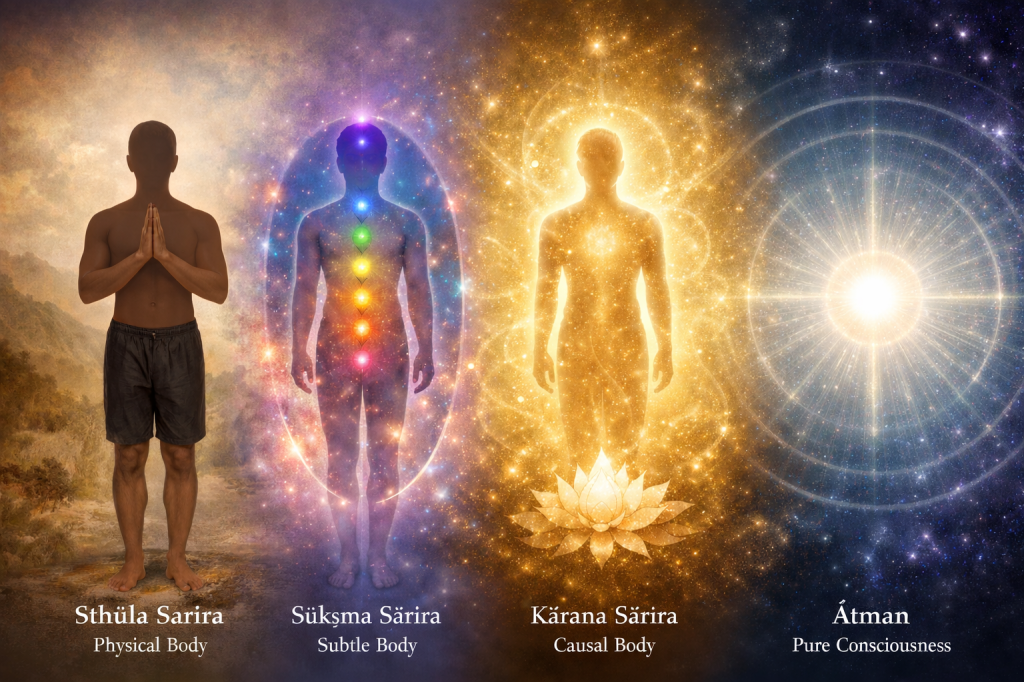

Let us understand the three layers of upādhis, or the three-body structure through which Ātman appears as the Jīva.

1. Sthūla Śarīra — The Gross Body

What is meant by Sthūla?

The word sthūla means gross, dense, tangible, extended.

It refers to that which:

- occupies physical space

- has measurable dimensions

- is accessible to the senses

- is subject to physical laws

The sthūla śarīra is therefore the visible, material body through which the Jīva engages with the physical world.

Nature of the Sthūla Śarīra :

Composed of Gross Elements (Pañca-bhūtas)

The gross body is constituted from the five gross elements:

- Pṛthvī (earth) – solidity, structure (bones, flesh)

- Āpaḥ (water) – fluidity (blood, lymph)

- Tejas (fire) – metabolism, temperature

- Vāyu (air) – movement, respiration

- Ākāśa (space) – cavities, extension

These elements combine to form a body that is:

- material

- perishable

- entirely within Prakṛti

Nothing in the gross body is independent of material causation.

Tangible, Visible, Measurable

The sthūla śarīra can be:

- seen by others

- touched

- weighed

- scanned

- medically analyzed

It has:

- height and weight

- age and appearance

- strength and weakness

This makes it fully objectifiable.

Anything that can be objectified cannot be Ātman.

Subject to Birth, Growth, Decay, and Death

The gross body alone undergoes:

- birth – appearance in space-time

- growth – increase and development

- change – maturation, transformation

- decay – deterioration

- death – disintegration

These changes are continuous and unavoidable.

Ātman, by contrast, is never subject to change. Therefore, the gross body is only an upādhi, not the reality.

Components of the Sthūla Śarīra :

A. The Physical Body

This includes:

- bones

- muscles

- organs

- tissues

- nervous system

It is the structural base of physical life.

When people say:

“This is my body”

They intuitively recognize it as possessed, not identical.

Yet habitual identification turns this possession into identity.

B. Sense Organs in Their Gross Form

The physical eyes, ears, nose, tongue, and skin belong to the gross body.

Important distinction:

- These organs are instruments

- The faculties of seeing, hearing, etc. belong to the subtle body

For example:

- A damaged eye prevents vision

- But vision itself is not the eye

Thus, the gross body supplies hardware, not cognition.

C. Organs of Action in Their Gross Form

Hands, legs, speech organs, and other motor organs are part of the gross body.

They:

- execute movement

- express intention

- carry out decisions

But intention itself does not arise here.

The gross body acts, but does not decide.

Function of the Sthūla Śarīra as an Upādhi :

The gross body serves three essential functions.

A. Localization of Experience in Space

Because of the body, experience appears localized.

You feel:

- “I am here”

- “That is there”

- “This pain is in my leg”

- “That sound is far away”

Without the body:

- there is no left or right

- no near or far

- no here or there

The body gives experience a spatial center.

This creates the basic sense:

“I am located at this point in space.”

This localization belongs to the body, not to Ātman.

B. Providing Physical Agency

The gross body allows:

- walking

- speaking

- eating

- working

- interacting with objects

Without the body:

- no physical action is possible

Even the strongest intention cannot lift a cup without a functioning body.

Thus, the gross body is the instrument of physical action, not the source of will.

C. Enabling Sensory Interaction with the World

Through the gross sense organs, the world becomes accessible.

For example:

- light strikes the eyes

- sound strikes the ears

- pressure contacts the skin

Without the body:

- there is no sensory world

- no form, sound, smell, taste, or touch

The body opens the gateway to the physical universe.

Identity Formation Through the Gross Body :

Because the gross body is the most obvious and persistent upādhi, identification with it is strongest.

From it arise statements such as:

- “I am tall / short”

- “I am young / old”

- “I am male / female”

- “I am healthy / sick”

- “I am strong / weak”

Notice:

- These are descriptions of the body

- Yet they are claimed as I

This is the first and most primitive layer of misidentification.

Why the Sthūla Śarīra Cannot Be Ātman :

This is the crucial discrimination.

The body is seen

You can observe your body:

- in a mirror

- in photographs

- through sensation

Its conditions are known

You know:

- hunger

- fatigue

- pain

- comfort

- aging

Whatever is:

- observed

- measured

- known

- changing

cannot be the knower itself.

Therefore:

The sthūla śarīra cannot be Ātman.

The Sthūla Śarīra as the Outermost Upādhi

Among all upādhis:

- the gross body is the outermost

- the most visible

- the most concrete

- the easiest to negate

This is why almost all spiritual inquiry begins here.

Yet negation does not mean rejection or abuse of the body.

The body is:

- respected

- cared for

- disciplined

—but not mistaken for identity.

In Summary :

The sthūla śarīra is the gross, physical body constituted of the five gross elements (pañca-bhūtas). It is the visible and tangible medium through which embodied existence operates. Through this body, experience appears localized in space as “here” and “there”; physical action becomes possible; and sensory interaction with the material world takes place. Without the sthūla śarīra, there would be no bodily agency, no physical action, and no access to the sensory domain.

Yet, despite its indispensability for embodied life, the gross body is entirely objectifiable. It can be seen, touched, measured, examined, and known. It is subject to continuous change—birth, growth, transformation, decay, and death. Because it is observable, mutable, and perishable, it cannot be Ātman. It is not the knower, but the known; not the experiencer, but the instrument of experience. For this reason, the sthūla śarīra stands as the outermost upādhi, the most external layer through which consciousness appears to engage with the physical world.

Never Forget :

The sthūla śarīra is insentient (Jaḍa). It does not think, remember, intend, decide, or store impressions. Memory, intention, and psychological continuity do not belong to the body. However, the gross body is the primary instrument of action. All physical actions—speaking, touching, moving, striking, restraining, protecting, helping, or harming—are executed through it.

While the body itself does not retain impressions, every action performed through it initiates karma. Karma does not remain confined to the external act; it registers in the inner instruments, shaping saṁskāras and, through repetition, settling as vāsanās. In this way, the sthūla śarīra functions as the gateway through which karma operates and enters the inner life, even though it is not the seat of karma itself.

Therefore, how one treats bodies—one’s own and those of others—matters profoundly. Physical harm, humiliation, neglect, or disrespect do not remain merely external events. They refine or distort the inner instrument depending on the nature of action. Acts of violence strengthen tendencies of anger, fear, and insensitivity; acts of care, restraint, and dignity cultivate steadiness, clarity, and receptivity for higher understanding.

Yama — The Law of Prakṛti :

Because the sthūla śarīra is the field of action (karma-kṣetra), the laws governing action must be understood and respected. The law of Prakṛti is not arbitrary; it is the fundamental order through which this creation maintains balance. Within this order, Yama functions as a universal discipline that regulates bodily conduct, speech, and outward behavior.

The five Yamas, as taught in the Yoga Sūtras (Chapter 2, Sūtra 30), are: Ahiṁsā (non-violence), Satya (truthfulness), Asteya (non-stealing), Brahmacarya (wise regulation of sensory and vital energy), and Aparigraha (non-possessiveness).

Yama ensures that interaction with the external world does not cause harm. These are not moral commandments imposed from outside, but natural alignments with the law of Prakṛti.

By living in accordance with Yama, one learns to engage with the physical world without aggression, exploitation, or disregard, even while recognizing that the world and the body are not the Ātman. This discipline allows one to fully acknowledge and respect the external world without becoming entangled in it.

Final Clarification :

The gross body is definitely not the Ātman. Yet it deserves ethical and disciplined treatment because it is the instrument through which karma unfolds and the field in which dharmic order is either upheld or violated.

Proper understanding (viveka) negates false identification with the body.

True discipline (Yama) governs how the body is used in the world.

Together, right understanding and right discipline ensure that one lives in the world without causing harm, acts through the body without accumulating bondage, and maintains inner order amidst external activity.

Only when bodily conduct is purified and harmonized in this way does awareness naturally withdraw from gross identification and become capable of recognizing the operations of the sūkṣma śarīra. Without such preparation, the subtle body (sūkṣma śarīra) remains obscured by gross impulses, and higher inquiry remains merely conceptual rather than experiential.

OṀ Tat Sat